The Plateau Effect

In almost every aspect of our lives, we experience the plateau effect at some point. Be it learning languages or a new skill, losing weight, training for a competition or even pursuing a romantic relationship. While we may progress quickly in the initial phases, we soon find ourselves entering a phase where there is no improvement. Our performance plateaus and sometimes, even regresses.

Similarly, we may have heard sayings that too much of a good thing can actually be bad. In a world where many struggle with insufficient sleep as we race to meet work deadlines, oversleeping is no less of an issue to contend with. In fact, oversleeping is linked with many of the same health risks as having insufficient sleep. This includes heart disease, metabolic problems such as diabetes and obesity, and cognitive issues including difficulty with memory.

Hence, finding the right balance to everything is not only optimal, to some extent, it is necessary. So necessary that the implications of adopting optimal balance can significantly change our world and those around us.

Of course, this is not for us to give reasons and excuses on why hard work is not all that effective, it is up to us to discover where the balance is and how we can make the best out of it.

The Context for Optimal Balance

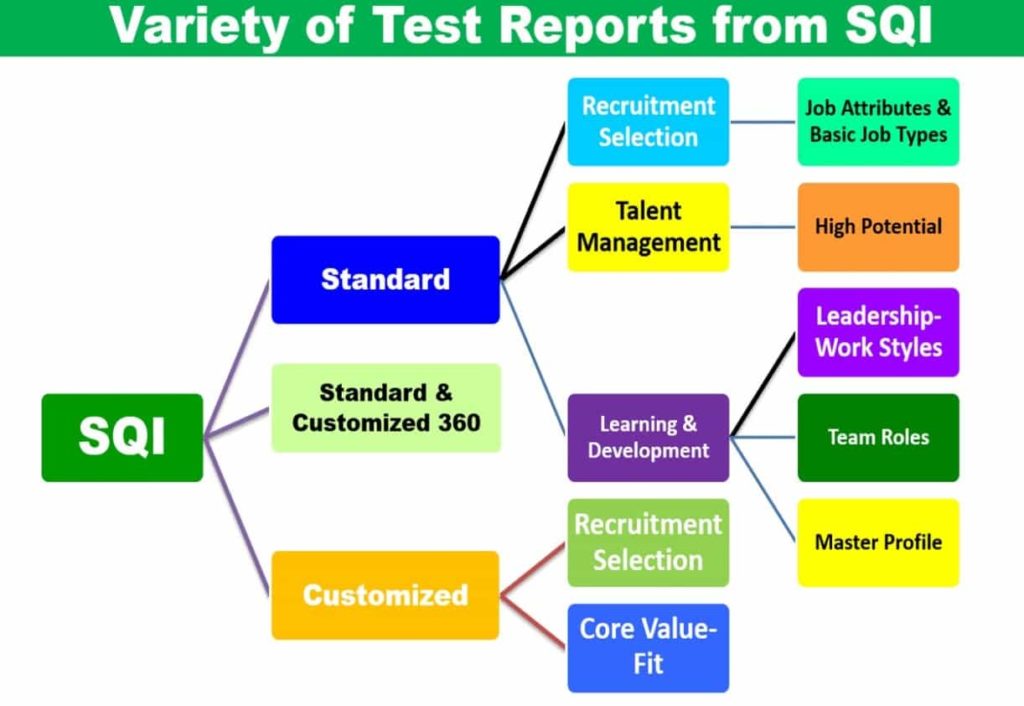

Recall the Barker & Bateson’s System Psychology model in Part 1. It is essentially the core approach of what SQI is rooted in. I.e. the effectiveness of a behavior is dependent on its fit with 3 aspects: “

(i) Nature of the work

(ii) People working together

(iii) Work environment

Based on this model, a person’s behaviour is manifested from a combination of various work personality trait inclinations. Therefore, he achieves optimal balance when there is a fit between his traits and the 3 aspects above. There is no predefined point or scores for the optimal balance as this model recognises the uniqueness of the individual and his work context.

Other Traits Assessment Models

Some models, such as the traditional bipolar model, assumes an either/or relationship. For instance, by placing Empathy and Enforcing on either end of the same scale, the bipolar approach assumes that the more empathetic you are, the less enforcing you will be and vice versa. By categorising individuals into either the “Empathetic type” or the “Enforcing type”, this approach misses valuable unique information about individuals who may possess both traits or score low on both. The idea of balance is not shown in such an assessment model.

Other models, such as the traditional paradox model, addresses the gap by distinguishing the primary traits and measuring them separately. However, they do not break down these traits further into sub-traits. For instance, Empathy (a primary trait) is not further analysed when a person has a low or high score.

Other models, such as the traditional paradox model, addresses the gap by distinguishing the primary traits and measuring them separately. However, they do not break down these traits further into sub-traits. For instance, Empathy (a primary trait) is not further analysed when a person has a low or high score.

This model assumes that high scores are good while low scores are bad. In this context, this model recognises that balance has been effectively achieved only when a person scores high on both paradoxical traits i.e. Empathy and Enforcing. While this assumption can be applied to ability assessments, the same cannot be said for our unique work personalities.

Finding the Balance

SQI has a Non-Evaluative Paradox model, primary traits are broken down into sub-traits. Each primary trait is measured along the choice between two sub-traits.

For instance, a person who scores high on Empathy adopts a Caring approach, while one who scores low on it adopts an Objective approach. A person who scores high on Enforcing adopts a Dutiful approach, while one who scores low on it adopts a Flexible approach.

Therefore, low scores do not prematurely judge the individual. For a person who often interacts with mature and able colleagues across different environments, having low scores on the Empathy and Enforcing traits may even support a fit in terms of his interpersonal relationships at work.

However, the indication of a low score brings value by highlighting to him how an observer may misunderstand his approach on showing Empathy, which is often associated with the inclination to be caring. Being aware of his workplace behavioural inclinations will better pre-empt him on areas requiring traits management, should there be changes in his work context. For instance, he may be transferred to a role requiring him to work closely with junior colleagues.

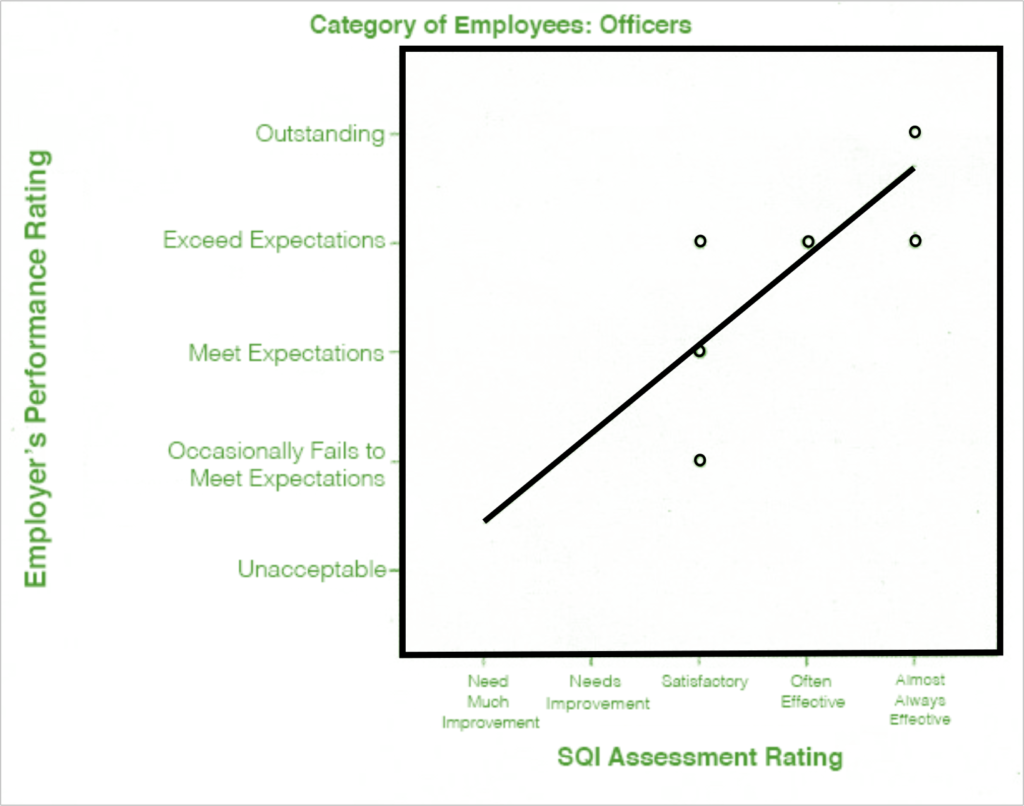

Actual Work Performance

Besides Work Personality Traits, actual work performance is an interaction of other factors. For a holistic interpretation of a person, we recognise that actual work performance is a function of these five factors: Psychological traits and behavioural tendencies, Skill Level (Vocational and Soft), Job Role Perception, Motivational factors as well as Family & Personal Variables.

Now combining SQI’s optimal balance principle with the choice-outcome assessment model, know that every theory has its unique value as well as its limitations SQI is not based on a single theory because we strongly believe in applying an integrated model in order to be holistic and representative. Therefore, it is a combination of established theories to gain a holistic view of psychology.

Within several professional bodies, many psychologists are still debating on different methods of measuring concurrent validity, construct and content validity. These debates pile on to the debate on various theories of psychology. SQI prefers to progress and perfect the work along the way rather than hold back valuable time debating on theories as there will be no final conclusion to that.

If you like the SQI system psychology perspective and the Non-Evaluative Paradox Model, do find out more about the “3 Things to Determine if a Personality Test is Accurate and Reliable”.

Awesome post! Keep up the great work! 🙂